|

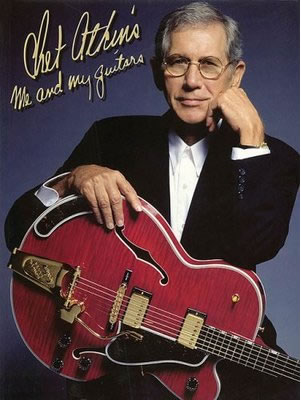

Chet Atkins BiographyFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Chester Burton "Chet" Atkins (June 20, 1924 – June 30, 2001) was an influential country guitarist and record producer in country music. His virtuoso picking style inspired by Merle Travis, Django Reinhardt, George Barnes and Les Paul, brought him admirers both within and outside the country scene. Chet Atkins produced records for Eddy Arnold, Don Gibson, Jim Reeves, Connie Smith, and Waylon Jennings to name a few. Atkins created, along with Owen Bradley, the smoother country music style known as the Nashville sound, which expanded country music's appeal to include adult pop music fans as well. BiographyChet Atkins was born in Luttrell, Tennessee, and grew up with his mother and siblings after the divorce of his parents. He started out on the fiddle, but traded his stepfather a rifle for a guitar when he was nine. Forced to relocate to Georgia to live with his father due to a near-fatal asthma attack, Chet Atkins was a sensitive youth who made music his obsession. He became an accomplished guitarist while he was in high school. Chet Atkins was self-taught, and later on in life gave himself (along with Tommy Emmanuel, Jerry Reed and John Knowles) the honorary degree "CGP", standing for "Certified Guitar Player". He didn't have a strong style of his own until he heard Merle Travis picking over WLW radio in 1939, when Chet Atkins was still living in Georgia. After graduating high school in 1942, his half-brother Jim, a successful guitarist (who worked with the Les Paul Trio in New York) helped get him a job at WNOX radio in Knoxville. There he played fiddle and guitar with singer Bill Carlisle and comic Archie Campbell as well as becoming a member of the station's "Dixieland Swingsters," a small swing instrumental combo. After three years, he moved to WLW in Cincinnati, Ohio, where Merle Travis had formerly worked. After six months he moved to Raleigh and worked with Johnnie and Jack before heading for Richmond,Virginia, where he performed with Sunshine Sue Workman, who soon fired him. Chet Atkins's shy personality worked against him, as did the fact that his sophisticated style led many to doubt he was truly "country." Relocating to Chicago, he auditioned for Red Foley, who was leaving his star position at the WLS National Barn Dance to join the Grand Ole Opry. Chet Atkins made his first appearance at the Grand Ole Opry in 1946 as a member of Foley's band. He also recorded a single for Nashville-based Bullet Records that year. That single, "Guitar Blues," was fairly progressive, including as it did, a clarinet solo by Nashville dance band musician Dutch McMillan with Owen Bradley on piano. Chet Atkins moved on to KWTO in Springfield, Missouri, but despite the support of executive Si Siman, soon was fired for not sounding country enough. While working with a Western Band in Denver, Colorado, Atkins came to the attention of RCA Victor. Si Siman had been encouraging Steve Sholes, to sign Atkins, as his style, with the success of Merle Travis as a hit recording artist, was suddenly in vogue. Sholes, A&R director of country music at RCA, tracked Atkins down to Denver. He made his first RCA recordings in Chicago in 1947. They did not sell. He did extensive studio work for RCA that year but had relocated to Knoxville again where he worked with Homer and Jethro on WNOX's new Saturday night radio show the Tennessee Barn Dance. In 1949 he left WNOX to join Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters back at KWTO. This incarnation of the old Carter Family featured Maybelle Carter and daughters June, Helen and Anita. Their work soon attracted attention from the Opry. The group relocated to Nashville in mid-1950. Atkins began working on recording sessions, performing on WSM and the Opry. While he hadn't had a hit record on RCA his stature was growing. He began assisting Sholes when the New York-based producer needed help organizing Nashville sessions for RCA artists. Atkins's first hit single was "Mr. Sandman," followed by "Silver Bell," which he did as a duet with Hank Snow. His albums also became more popular. In addition to recording, Atkins became a design consultant for Gretsch, who manufactured a Chet Atkins line of electric guitars from 1955-1980. Atkins also became manager of RCA's Nashville stuido. When Steve Sholes took over pop production in 1957, a result of Sholes's success with Elvis Presley, he left Atkins in charge of RCA's Nashville division. It was then that Atkins and Owen Bradley, seeing country music record sales in tatters as rock and roll took over, came up with the idea of eliminating fiddles and steel guitar as a means of making country singers appeal to pop fans. Atkins used the Jordanaires and a rhythm section on hits like Jim Reeves's' "Four Walls" and "He'll Have to Go" and Don Gibson's "Oh Lonesome Me" and "Blue Blue Day." The concept of having a country hit "cross over" to pop success became a formula. He and Bradley had essentially put the producer in the driver's seat, guiding an artist's choice of material and the musical background. Atkins made his own records, which usually visited pop standards and jazz, in a home studio, recording the rhythm tracks as RCA but working on them repeatedly until they satisfied him. Guitarists of all styles came to admire various Atkins albums for their unique ideas and in some cases experimental electronic ideas. He enjoyed jamming with fellow studio musicians which led to them being asked to perform at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960. That performance was canceled, however, due to rioting. Atkins performed at the White House in 1961. Before his mentor, Sholes, died in 1968, Atkins had become vice president of RCA's country division. He had brought Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Connie Smith, Bobby Bare, Dolly Parton, Jerry Reed and John Hartford to the label in the 1960s. He took a considerable risk during the mid-1960s, when the Civil Rights Movement sparked violence throughout the South by signing country music's first African-American singer: Charley Pride, who sang rawer country than the smoother music Atkins had pioneered. But Atkins's hunch paid off. Ironically, Pride's biggest fans became the most conservative country fans, many of whom didn't care for the pop stylings Atkins had added. Atkins's own biggest hit single came in 1965, with "Yakety Axe," an adaptation of his friend saxophonist Boots Randolph's "Yakety Sax." He rarely performed in those days, and eventually had to hire other RCA producers like Bob Ferguson and Felton Jarvis to allieviate his workload. In the 1970s, Atkins became increasingly stressed out by his executive duties. He produced fewer records but could still turn out hits such as Perry Como's pop hit "And I Love You So." He recorded extensively with close friend and fellow picker Jerry Reed, who'd become a hit artist in his own right. A 1973 bout with colon cancer, however, led Atkins to redefine his role at RCA, to allow others to handle administration while he worked more on his music, often recording with Reed or even Homer & Jethro's Jethro Burns (Atkins's brother-in-law) after Homer died in 1971. By the end of the '70s, Chet Atkins's time had passed as a producer. New executives at RCA had different ideas. He retired from his position in the company. Then began feeling stifled as an RCA artist because they would not let him branch out into jazz. At the same time he grew dissatisfied with the direction Gretsch, no longer family-owned, was going and withdrew his authorization for them to use his name and began designing guitars with Gibson. He left RCA in 1982 and signed with Columbia Records, for whom he produced an album in 1983. While he was with Columbia, he showed his creativity and taste in jazz guitar, and in various other contexts. He did return to his country roots for albums he recorded with Mark Knopfler and Jerry Reed. Chet Atkins received numerous awards, including eleven Grammy Awards and nine Country Music Association Instrumentalist of the Year awards. While he did more performing in the 1990s his health grew frail as the cancer returned and worsened. He died on June 30, 2001 at his home in Nashville. Before his health drastically declined, Atkins authored a book on his music and his extensive guitar collection for publisher Russ Cochran. In his final recollection, he stated: |